CARTE BLANCHE: "WORLD WAR II FILMED BY AMATEUR FILM-MAKERS, A DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVE ON THE CONFLICT" - BY MARC POTTIER, HISTORICAL ADVISOR

In 2024, the round of commemorations marking the 80th anniversary of the Liberation of France commenced in Corsica. Following this, there were memorials to pay homage to the foreign heroes of the Resistance, honour the memory of the great Maquis forces and remember Holocaust victims. Remembrance ceremonies then took place in Normandy, to mark the strategically important D-day landings, before culminating in the commemoration of the end of World War II in Europe. Alongside these ceremonies, the Amorce platform, which showcases over 200 films created by amateur film-makers from 1937 to just after the war, is an exceptional tool to learn more and pass on knowledge about this period, while offering a different perspective on the conflict.

Too often, in our collective memory and imagination, the Second World War is reduced to a list of dates, strategies, troop movements, famous speeches and major historical figures. These common references in our minds come from official images produced for news bulletins at the time, or filmed by members of the armed forces. This archive footage, which we generally find in historical documentaries, television programmes and museum exhibitions, shapes our vision of the war.

Our other moving picture references are influenced by Hollywood cult movies like The Longest Day, by Darryl F. Zanuck (released in 1962) and Saving Private Ryan, by Steven Spielberg (released in 1998), or by serials like Band of Brothers, created by Tom Hanks and Steven Spielberg (aired en 2001 on HBO), or by video games like Medal of Honor (released in 1999) or Call of Duty WWII (released in 2017).

With all these visual representations of Second World War history, what more can films produced by amateur film-makers offer us? How can these private films and family footage provide a fresh perspective and bring us closer to a form of “raw history”, by immersing us in the long, ambiguous “dark years” of the Occupation and the subsequent Liberation of France?

First of all, these amateur films are an act of memory. Amateur film-makers seek to capture a major historical event, to show History in the making. Another important motive is to make their mark, to pass on the extraordinary moment they have experienced, to make sure it will not be forgotten. When families and individuals are faced with exceptional events, film-makers grab their cameras and record what they see.

Thirteen film libraries have chosen to showcase an archive of amateur films that characterise these moments of turmoil, these turning points in history.

One important, much-filmed moment is the “strange defeat” in 1940. The debacle of the French army in a matter of weeks, the fall of France and the arrival of German troops are depicted in Fernand Bignon’s film, Communion, Normandie Images.

This film connects the family’s private history with the remarkable events taking place at the time. On Sunday 19 May 1940 at Gisors (Eure - Normandy), Jacqueline Bignon received her first communion. As usual, her father Fernand, who had been a professional photographer in this major town since the early 1930s, filmed this important moment in the life of his beloved daughter.

In the background, he also captured the lives of Gisors residents during the weeks when the battle of France took place and the French army was defeated. Alongside the private communion ceremony, columns of vehicles pass in the street. They are carrying refugees from Holland, Belgium, Luxembourg and northern France, who are passing through the town. During the last three weeks of May 1940, one million refugees flocked to the area, either taking refuge in the Eure region or passing through it.

Another film, Seconde Guerre mondiale à Charlieu, Cinémathèque de Saint-Étienne also shows the fall of the French army, which was considered the most powerful army in the world until May 1940. Columns of cars and vehicles carrying refugees pass through Charlieu, a town in the Loire region, just before the arrival of German troops.

Another important aspect of the war, to which many films bear witness, is the presence of the occupying forces.

Images of German troops are the most visible evidence of occupied France. They show France “under the Germans” and are even more significant because the German occupying authorities issued a decree on 22 October 1940 stipulating that “taking any kind of images using any gauge of small-format films was prohibited”.

Shopkeepers were not allowed to sell reels of film, or to develop or print 8 mm, 9.5 mm or 16 mm images for any customers except for German soldiers. In addition, it was hard to obtain raw materials, films and chemicals due to supply difficulties.

And yet people risked their lives, despite the shortages, to make films during the war. The film Arrivée d'une colonne allemande, CICLIC, which was shot by Maurice Raby, hidden behind his window in Châtillon-Colligny, clearly illustrates the need to bear witness to the situation, despite the danger. Even though filming was forbidden, people used cameras as an outlet, a way to demonstrate their disagreement and opposition to the invasion of the Occupying forces into their personal lives. These films were in fact a form of civilian resistance, a citizens’ commitment to document events with their cameras, not only to record and describe the situation but also to show their objection to it.

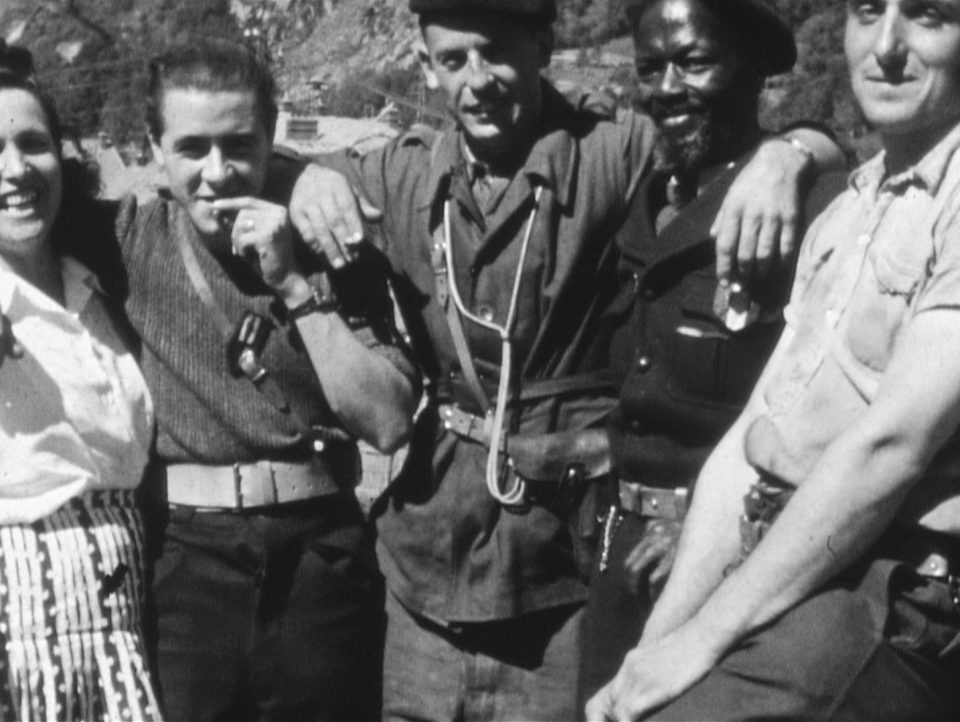

One archetypal film in the “opposition to the Occupation” category is undeniably Maquisards de Maurienne, Cinémathèque des pays de Savoie et de l'Ain, a true work of resistance behind the camera. The Resistance fighter and film-maker Eugène de Grolée-Virville filmed the daily activities of the Stéphane company of Resistance fighters from the Grésivaudan battalion, showing their camps, movements and training during several ambushes and battles in the Savoie region of the French Alps. These images are truly exceptional, a powerful and rare portrayal of Resistance fighters.

Another much-filmed turning point was the Liberation of France. Three films - Seconde Guerre Mondiale à Charlieu, Cinématèque de Saint-Etienne, Liberté retrouvée : La libération de Candas et le retour des prisonniers, Archipop and Catastrophes, Mémoire des Images Réanimées d'Alsace - recall the unforgettable scenes of jubilation, the hugs and the warm handshakes that characterise the long-awaited arrival of the Allied Liberation forces. In the liberated towns and villages that had not suffered too much during the war, the streets erupted in joy. People hastily made banners praising the Allied forces, as well as flags or even dresses with the Union Jack or the Stars and Stripes. They also flew the French tricolour flag with the Lorraine Cross.

But all too often, the Liberation was also a time of suffering and devastation. Aron après la tourmente, Ofnibus - Résidence d’archives itinérante, depicts the martyred village of Aron in the Mayenne region. The village was the scene of incessant fighting between German and American forces from August 5 to August 13, 1944. Thirty-one people, who lived or had taken refuge in Aron, perished during this week of bloodshed; eighteen were killed in bomb attacks, while thirteen succumbed to Nazi barbarism.

Brest en ruines, Cinémathèque de Bretagne tells a similar story, and shows the price paid for freedom. On 18-19 September 1944, Brest was liberated following six weeks under siege. But the city suffered heavy losses. Brest was completely devastated by Allied bombing and German destruction: 428 lives were lost, 5,000 buildings were destroyed, the port was inaccessible, 2,000 wrecked ships lay in the bay, the naval dockyard was no more, 80% of the city lay in ruins. Ruines et deuils ou les Vosges sinistrées, Image'est also shows the devastation following the fierce fighting in Saint-Dié-des-Vosges, Épinal, La Bresse, Charmes and Rochesson. The Battle of the Vosges, from September 1944 to February 1945, was the first time the advancing Allied forces met any real opposition from the German army after the collapse of the Normandy front. Fighting between American, French and German troops was particularly fierce, and the harsh winter of 1944-1945, in the Vosges mountains, made the situation even more difficult. The archive film by Reverend Joseph Danion, Father Superior of the Domrémy Basilica, illustrates the difficulties and consequences of this battle, and the “price paid” to win back freedom.

At last, the Armistice agreement was signed. The film 8 mai 1945 à Genève, Fondation Autrefois Genève, clearly portrays this moment of immense joy, relief and shared hopes for peace in Europe following the surrender of Nazi Germany. And yet wartime was not over, and life could not resume as it was before.

It was now time for war prisoners, forced labour conscripts and deportees to return home, as shown in La libération de Candas et le retour des prisonniers, Archipop. Although towns and villages joyfully welcomed their sons and survivors home after such a long absence, with parties and parades, in actual fact these homecomings were difficult. In particular, the soldiers who were “taken prisoner in 1940” were still associated with the French defeat five years earlier. Other male role models, such as Resistance fighters inside and outside France, had taken centre stage in French post-war society.

And before life could return to normal, much work had to be done to try to erase the physical scars of war. This is shown in the film Déminage de la plage du Touquet, Cinéam-Archives audiovisuelles en banlieue parisienne. Clearing mines, defusing bombs, removing shells, destroying the hundreds of thousands of deadly devices that remained on beaches, in fields, in hedgerows and among ruins, was an essential first step. This was such a major problem that a bomb disposal authority was created within the Ministry of Reconstruction and Town Planning. It was headed by the famous Resistance fighter Raymond Aubrac. To carry out this dangerous work, German war prisoners were employed alongside voluntary mine clearers. They all suffered very heavy losses. Five hundred French mine clearers and over one thousand eight hundred prisoners died in the course of their duties.

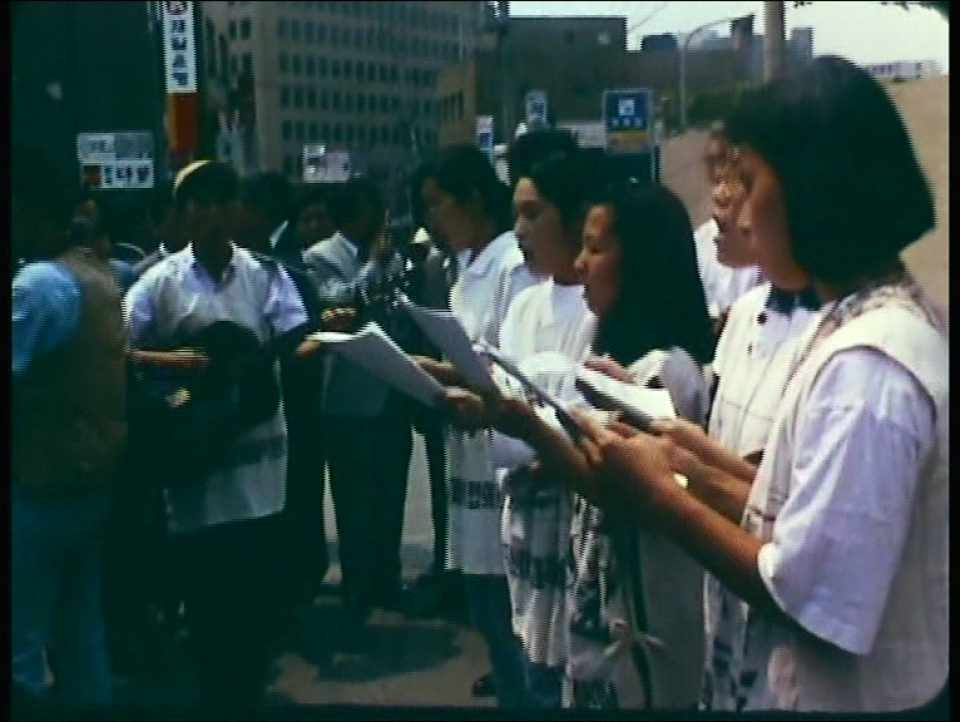

The war also left people with other long-term scars. Murmures, une histoire de femmes coréennes, Centre Audiovisuel Simone de Beauvoir, bears witness to the suffering of Korean women who were forced into prostitution for Japanese servicemen. The wounds and shame left by sexual slavery, and the refusal of the Japanese authorities to recognise the crimes and abuses committed against these women, nor against the civilians massacred in Nankin (China), means that decades after the war, the “past cannot be laid to rest”. This film implicitly addresses the issues of recognition and justice. Murmures, une histoire de femmes coréennes, also reminds us that the war affected the whole world, and that other aspects of the conflict also form its film heritage.

Another facet of life during the war can be found in the film Diverses images de l'armée allemande, 1944, La Cinémathèque de Montagne. Filmed by a German officer, this footage of a regiment’s daily life - travelling, during leave, at rest, or enjoying a Christmas feast - shows soldiers from the other side, German enemy forces. What we see is really quite ordinary, and resembles the daily life of all armed forces. But behind these commonplace images, you cannot help asking yourself what these soldiers did during the war. Did they take part in the mass killings on the Eastern Front or commit atrocities elsewhere?

This brings to mind Christopher Browning’s book: Ordinary men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland. With no information on this regiment, and without knowing what these men actually did, this film implicitly addresses the important issue of “normalising” assassins and their evil acts, as do other films showing German soldiers, such as Catastrophes, Mémoire des Images Réanimées d’Alsace or Arrivée d'une colonne allemande, CICLIC.

Passing on history and ensuring that we will never forget are clearly the watchwords of these unique, exceptional archive films.

The World War II film collection on the Amorce platform truly endeavours to portray history and foster remembrance. By recording daily life faced with the tribulations of war, these amateur film-makers sought to leave a historical testimony, to pass on family heritage, and showed their passion for film-making. We instinctively feel empathy for these film-makers, with their desire to capture fleeting moments, because the generation behind the camera are our parents or grandparents.

Although we cannot always decipher, interpret or place these amateur films in their historical context, they remain powerful with their intimate portrayal of family and friends, who often look straight at the camera - confidently, shyly, kindly, or with an embarrassed or funny look - making these moments in history palpable and moving.

Family footage is not just an anecdotal addition to the great book of History, it undeniably offers another perspective, an essential counterpoint to official images and statements, a new way to show the past, by taking a close-up of real life throughout history. The Amorce regional film heritage platform is therefore a unique, exceptional resource.