CARTE BLANCHE "WOMEN IN AMATEUR, INSTITUTIONAL AND ACTIVIST FILMS", BY TERESA CASTRO, A LECTURER IN FILM AND AUDIOVISUAL STUDIES AT THE SORBONNE NOUVELLE UNIVERSITY

When you delve into amateur film archives, you meet a whole range of women. Women from different backgrounds and social classes: Arlette, the vivacious daughter of the Pathé engineer Georges Moreau, dancing the Charleston in a cabin on Noirmoutier beach (Arlette danse le Charleston dans la cabine sur la plage de Noirmoutier, 1926, Cinéam); or Fine, the sea boatwoman (Fine, Jo et Yvon Potier, 1973, CDB). Women together, in groups, working, demonstrating, playing rugby, basketball or football (L’équipe féminine du Stade de Reims en Espagne, Pierre Geoffroy, 1972, Image’Est). Female workers, peasants, farmers, typists, housewives, prostitutes. Women laughing and having fun together, like the workers at the Lumière factory (Les Catherinettes des Usines Lumière, Inconnu, 1950, CPSA). Remarkable individual women, noted for their words or actions, like Flo Kennedy, an African American feminist activist (Flo Kennedy, portrait d’une féministe américaine, Carole Roussopoulos, 1982, CaSdB). Women whose status as the wives, mothers or daughters of an eager or affectionate film-maker ensured that the fleeting passage of their lives was recorded on film. For example, Roger Minet’s wife (Une Femme, 1977, Archipop), Jean Kleinknecht’s mother (Aimée Kleinknecht née Marchal, 1950-1966, MIRA), Henry Debrie’s daughter (Entre Scholistes, 1930, Cinéam). Women who were famous in their era, then so often forgotten as time passed, like the tennis player Simonne Matthieu (Simonne Mathieu contre Henri Cochet au tennis club de Béziers, Ralph Laclôtre, 1932, MIRA). And women about whom we know nothing, except for the smiles, gestures and expressions in their eyes that we glimpse in these films.

As this selection of films compiled by the Diazinteregio network shows, when you delve into amateur film archives, you explore large swathes of women’s history in France during the 20th century. Every facet of their daily lives is present - work, travel, politics, sexuality, health - even though there are still a few grey areas. When you watch these films, you experience the specific characteristics and issues of women’s history, including the host of stereotypes that surround them. For example, Sois belle et tais-toi ! (Be beautiful and be quiet!), in Delphine Seyrig’s film (1976, CaSdB). Women’s history is confronted with the disparity between the prolific number of images and discussions on women and the lack of actual, detailed information on these same women. But these films also invite us to think about the wider history of cinema and film-making. Amateur film-making, this “other” form of cinema, challenges the idea that the history of cinema can be written by historians alone: archivists, film programmers, actors, film-makers and spectators also play their part.

Amateur film-making is a valuable resource to study the transformation of women’s status in society throughout the 20th century. From the late 1920s onwards, these films show women in a working environment, especially in industrial firms, where they represented a large, well-disciplined proportion of the workforce. They performed specific tasks, such as reeling, knitting and making textiles (Les établissements Lévy à Saint Max, Pierre Claudin et Charles-André Doley, 1929, Image’Est), lining felt hats (L’industrie du chapeau, Max Dianville, 1930, CSE), or brushing and canning tuna (Travail de la sardine et du thon, Jehan Courtin, 1942, CDB). The film Catherinettes des Usines Lumière, which depicts a beautiful moment of companionship between fellow female factory workers - as well as showing the conservative post-war values regarding gender roles and sexuality - is also a reminder that the majority of employees throughout the history of this famous factory in Lyon were women. We don’t know who filmed these rather unsteady images with a hand-held camera. A few shots are in slow motion, as if the film-maker had pressed the wrong button by mistake. Do we have to assume, as we almost always do, that the “anonymous” person behind the camera was a man? Why not a woman, who improvised on this day of celebration? A woman holding a camera, filming playful, intimate images of her colleagues as best she can, as she moves among them. How many amateur films, which we assume were made by the father of the family, might actually have been filmed by his wife? And what about other contributions, like making title cards or editing films?

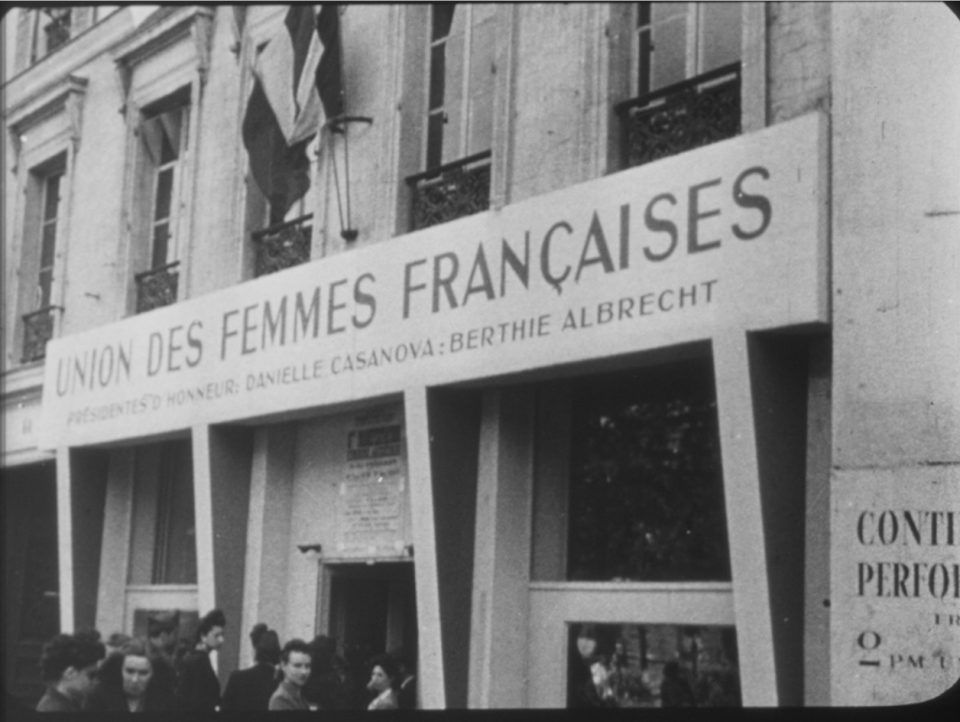

After the Second World War, amateur and activist films bear witness to the advancement of women’s rights and feminist movements. In Jour de vote à Thaon-les-Vosges (Lucien Perrot, vers 1946, Image’Est), a woman proudly places her voting slip in a ballot box; in Manifestation des ménagères féroises (Pierre Lebrun, 1946, Archipop), housewives are on strike. The group that recorded this transgressive event was banned by the French police. This demonstration was probably connected with the rapid expansion of the Union des Femmes Françaises (UFF - Union of French Women). With over a million members, this organisation brought together women’s committees from all around France (which had been very active during the Resistance), under the supervision of the French Communist Party. The UFF held its first convention in June 1945, as reported by the film 1er Congrès des Femmes Françaises (1945, Ciné-Archives), with a commentary by actresses Cécile Didier and Renée Simonot. The film was edited by Simone Dauvillier. We still know practically nothing about the numerous female editors who worked on films in France from the 1920s onwards. Women film-makers or editors - both amateurs and professionals - have often been erased from records.

Following the 1930s and 1940s, when women played “barette”, a form of rugby, in Saint-Etienne (Ciné-Journal de Saint-Etienne 1930, Office du cinéma éducateur de Saint-Etienne, Eugène Reboul, 1930, CSE) and Simonne Matthieu won two French singles tennis titles (the 3rd show-court at Rolland Garros was named after her in 2017), the following decade marked a return to particularly conservative stereotypes. Women’s history is peppered with such advances and setbacks. Of course, women continued to play sports and defy restrictions, but gender constructions started to follow the sexist dictates of the consumer society. One example is the promotional film that a certain Jean Suberbie produced for various shops in Guingamp, Rencontre (1956, CDB). Although Yvonne is shown looking at typewriters to “type faster and quicker”, she seems to be destined for life as a housewife. As a “shrewd homemaker”, she seeks products that “make housework enjoyable”, stroking fridges and washing machines. The housewife was a regular figure in many amateur films for a very long time, and every so often she was portrayed in a loving, tender way, for example La journée de maman (Martial Debros, 1960, Mémoire Normandie). In this film, we witness the domestic chores, the invisible, “natural” work of women, for which they are not paid. As Silvia Federici wrote: “They say it is love. We say it is unwaged work.” In Des femmes du Haut-Quercy (1975, CaSdB), Catherine Lahourcade and Syn Guérin clearly show that the work done by the (elderly) wives of farmers and breeders forms the cornerstone of the household’s budget. Because amateur films (and especially family footage) grapple directly with the realities and prejudices of their time, they paint a much sharper picture of gender constructions, gender hierarchy and sexism. In other words, they show the predominance of men in society.

It was not until the 1970s that the increasingly prominent women’s liberation movement, with its feminist debates, started to make waves. The Centre Audiovisuel Simone de Beauvoir holds a particularly rich collection of unique images of these years of activism, action and revolt. These films are even more valuable because passing on the heritage of feminist activism is now a major issue. At the time, women campaigned for the right to contraception and abortion, and against various forms of oppression and misogyny. In the wake of May 1968, there was a wave of strikes, like the one at the Lip factory in Besancon (Monique – Lip I, Carole Roussopoulos, 1973, CaSdB). Feminists also campaigned internationally: they fought for female writers in Portugal, for women activists in Brazil, for mothers and sisters in Spain. These films allow us to meet important figures in feminism and the North American civil rights movement: Kathleen Cleaver, Flo Kennedy, Ti-Grace Atkison, Kate Millett. Above all, women took control of film-making equipment, trained themselves and produced their own films to support the causes they were fighting for. Numerous video collectives were formed: as women got behind cameras, they were no longer just portrayed in films, but took ownership of the images they filmed. They broke the silence that was symbolically imposed upon them. In Lyon, the prostitutes that were occupying a church finally had the right to speak (Les Prostituées de Lyon parlent, Carole Roussopoulos, 1975, CaSdB). In Britanny, a group of women from Quimper, the Finistère family planning service and the Atelier de Création Audiovisuelle Saint-Cadou talked openly about their bodies and denounced attitudes in the healthcare system (Clito va bien, Groupe Femmes, 1979, CDB). Amateur female film-makers followed suit, but remained more enigmatic: in 1985, five women discussed their personal situations in Cinq bobonnes à la une (Robert Parlange, 1985, CICLIC).

The question of who authored films is not a trivial one. In amateur films, women were often filmed by men. But women had already started filming long before the feminist movements of the 1970s. Although professional and institutional film-making may have been less accessible, women from the wealthy middle classes turned their cameras on the world around them. They filmed their holidays (Pornichet 1930-1932, Odette Guilloux, CDB), produced almost ethnographic portrayals of communities (Couture-Boussey, Yvette Ripplinger, 1952, Mémoire Normandie), or even staged their own appearance in front of the camera (Marcelle Verelle en Vacances, 1957, Image’Est). As this last film shows, these women were not necessarily challenging cultural gender models, but they did demonstrate their desire to “do a professional job”, like many other amateur film-makers. Without realising it, by making their mark, they helped redress the unequal balance that hangs over the history of women. They filmed their friendship, or even sorority (Vacances Sainte-Marie-de-la-Mer, Odile How Shing Koy, 1973, CSE). Holding their Super-8 and video cameras, they took part in various demonstrations, like the major protest march linking feminism, nuclear disarmament and ecology (Marche des femmes pour la paix de Copenhague à Paris en 1981, Solange Fernex, 1981, MIRA).

These new resources, which digitisation has made more accessible, invite us to imagine new versions of history, to question dominant narratives and, above all, to take an active interest in various aspects of women’s lives and their contribution to film-making. Because women were always involved in film-making, more than we might have thought. (Re)writing history can be a benevolent process: a way to set things right, attract attention or increase awareness. And this can be done in a rigorous, meticulous manner that leaves room for complexity, reflection and above all, imagination. That is what this selection of films invites us to do.