CARTE BLANCHE: RECONSIDERING “PROGRESS” IN TRANSPORT NETWORKS THROUGH REGIONAL FILM HERITAGE

By Cyprien Richer, research fellow, CEREMA, CY Cergy Paris University; MATRiS Laboratory (Mobility, Urban Planning, Transport, Risks and Society), 59000 Lille, France, 03/11/2025.

“He who does not move forward, falls behind progress.” This quote comes from the voice-over in a film from Fondation Autrefois Genève about the Genevan transport network (1963). It conveys the idea that progress is intrinsically linked to movement and that standing still actually means moving backwards as history unfolds. Mobility does not just involve transporting people and goods; according to Arnaud Passalacqua, it also embodies political ambitions, economic aspirations and beliefs in material progress.[1] The industrial revolution gathered speed with the arrival of railways (transporting people, energy and goods); the “golden thirty” postwar years catapulted us into a more liberal, global economy, epitomised by the motor car; and finally modern times shaped our fast-moving, ultra-urbanised, yet increasingly vulnerable world.

This selection of 15 archive films invites us to explore sixty years of major transformations in the transport sector from the 1920s to the early 1980s. They show major developments in transport from the industrial era (trams, trains, waterways) through to widespread car use at the end of the 20th century. One of the most interesting aspects of this patchwork of films is that they illustrate different phases in the development of transport networks. As a matter of fact, research into transport draws on the network theory developed by Gabriel Dupuy,[2] and specifically on the generic model for technical networks – including transport networks. Each one of these films portrays one particular phase in the development of a transport network from different angles: infrastructure (canals, railways, roads, etc.), vehicles (trams, buses, hovercraft, hovertrains, barges, etc.) or services (mobility management and regulation).

The generic network development model, adapted from an article by Jean-Marc Offner,[3] can be summarised by the following phases: “incubation” (0) of the transport project before it enters service, which may involve tests and innovations; “launch” (1) of the new network, when commercial operations commence; “initial development” (2), which may result in rapid growth if the conditions are right; “maturity” (3), when the network reaches its peak, which may entail market domination or monopoly; “decline” (4), which often occurs due to internal or external competition and requires the network to be transformed or restructured; and finally, if this reorganisation does not produce the desired results and enable the network to reach a new equilibrium, the final phase is “closure” (5).

The films collected by the film libraries and archives in the Diazinteregio network, and shared on the Amorce platform, offer a condensed vision of each phase in transport network development.

– Network incubation phase (0)

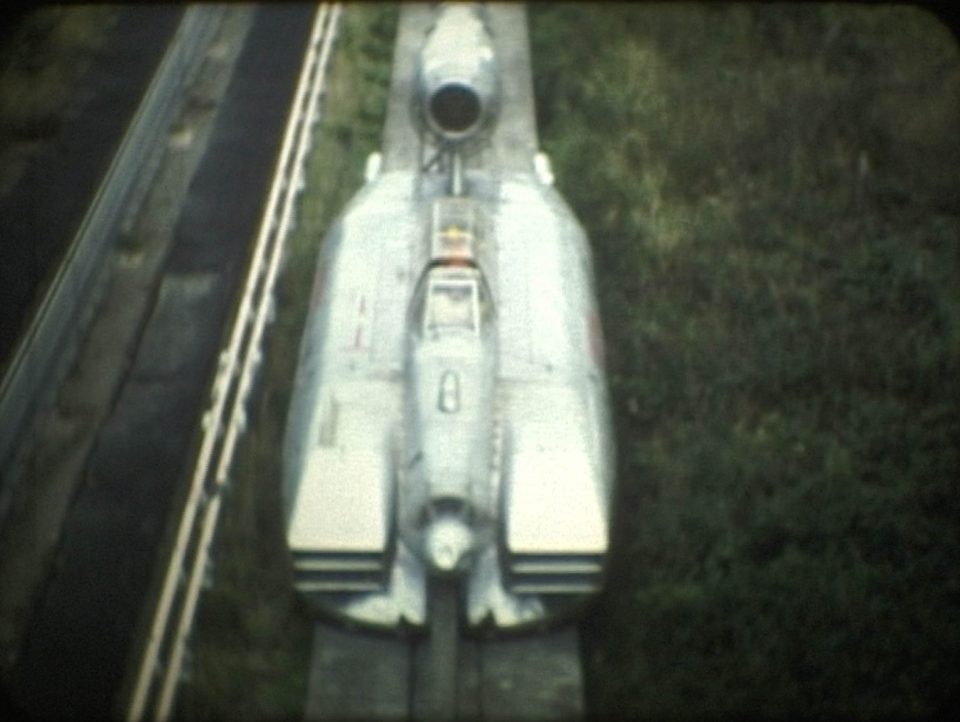

Before an invention is launched, there is always an incubation phase. The most famous project incubation was the hovertrain designed by the engineer Jean Bertin, as shown in this film from Cinéam-Mémoire filmique d'Île de France. This documentary revisits the first full-scale tests from 1965 onwards on an experimental section of track between Gometz-la-Ville and Limours, in the southern suburbs of Paris. Described as a “beautiful utopia”, the hovertrain illustrates the French proverb: “We don’t have oil, but we have ideas!” At the time, when the oil crisis prompted countries like Holland to control the use of fuel-driven vehicles and revive bicycles, France built a myth on the invention of cutting-edge transport systems, as Arnaud Passalacqua notes in his work. This national narrative led to the creation of superb technological solutions to solve badly defined social issues. Incidentally, the hovertrain was never actually launched as a commercial service.

Another vehicle in incubation was the fanciful Carling Home No. 2, invented by Charles Louvet (1929), portrayed in this film from MIRA, the Alsace regional digital archive. In this film, we see the ancestor of the modern camper van driving around. This futuristic vehicle, inspired by aircraft, was 10 metres long. Although the first models of residential vehicles homes had been around since the beginning of the 20th century, it was only after the war, in the 1950s, that such vehicles were mass-produced as the context became more favourable for motor tourism.

– Network launch phase (1)

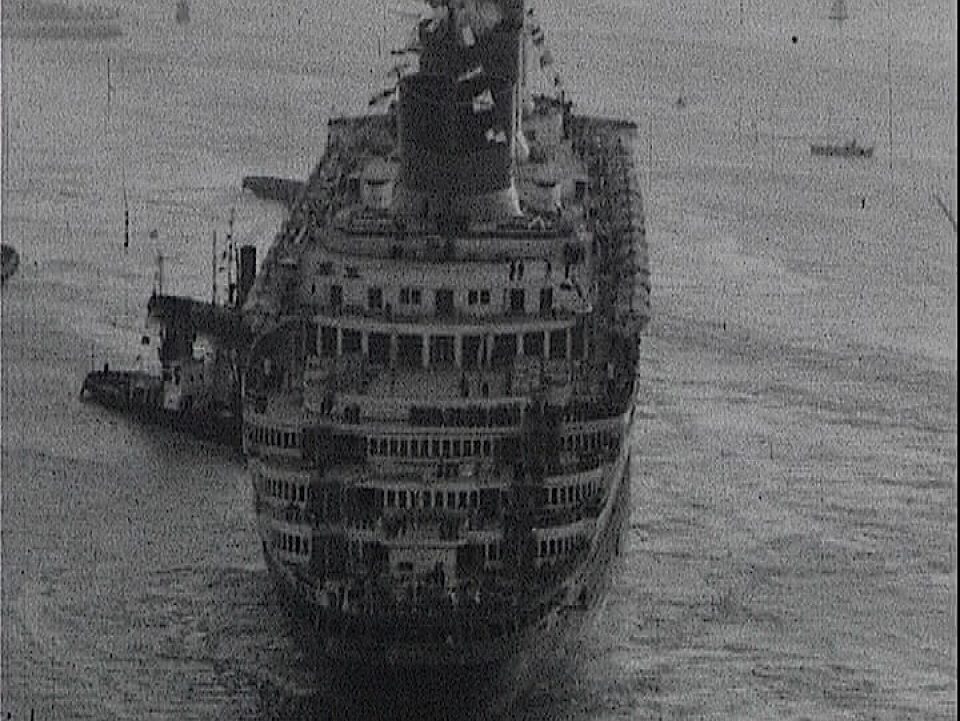

Launching a new mode of transport is a significant moment when passengers discover a vehicle for the first time. This film from Normandie Images portrays the maiden voyage of the Normandie ocean liner (1935), which was the pride and joy of France. Built in Saint-Nazaire shipyard between 1931 and 1935, she became the largest passenger ship in the world when she entered service. Although she was a symbol of modernity and power, the liner was only in service for a few short years until commercial passenger services stopped when war broke out in 1939.

Another quite different maiden voyage, this time on the Lille light railway (1982), which was also the pride and joy of the Lille metropolitan area. The technology for this light automated transit system (VAL) was created in the early 1970s at Lille University, by Professor Gabillard’s team. The first curious passengers share their impressions in this film from the ARCHIPOP association, which provides an interesting insight into the adoption of modern technology by the population of a fast-changing city. In fact, advocates of the VAL light railway believe that it symbolises Lille becoming a metropolitan city.

– Initial development phase (2)

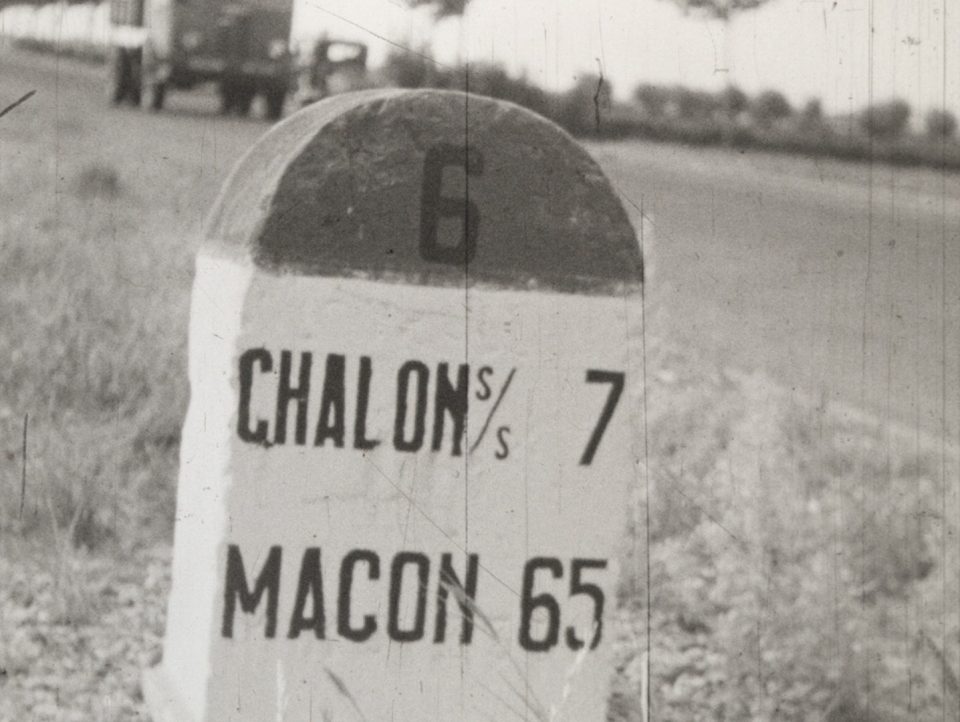

The films portraying the initial development of a network between 1930 and 1950 are about motor cars. Two archive films from the 1930s, from the Cinémathèque de Saint Etienne and CICLIC Centre-Val de Loire, show road accidents. This demonstrates that infrastructure was not yet adapted to motor cars, and that garages, petrol stations, breakdown recovery and emergency services were still underdeveloped. From the early 20th century onwards, the “Touring Clubs” and Automobile-Club de France encouraged people to take up motor tourism. The first Michelin Guide was published in 1900, which helped set up a signage system (road signs, signposts, maps), and assisted motorists in locating technical facilities (petrol stations, garages) and places to stop (hotels, restaurants). The essential components of the “motoring system” were installed, allowing car tourism to expand rapidly. Once the war was over, everything was ready for a massive increase in car use. This film from the OFNIBUS association shows a holiday trip in 1949 from Paris to a small village in the Jura region. Here, the car is depicted as a prized possession, which takes centre stage throughout the trip. Road signs, placed at eye level for drivers, indicate the new geography of provincial France. The modern motor car contrasts with the hand carts, horse-drawn carts, bicycles and donkeys in the villages along the way. Some people might see two sides of France: on the one hand, urban civilisation, with its modern motor cars, initially reserved for the elite; and on the other, rural villages, which still relied on outdated modes of transport. This is an oversimplified vision, since motorisation would soon sweep through the countryside; in fact, 1957 saw record sales of tractors.[4]

– Network maturity phase (3)

The network maturity phase is particularly well illustrated by this film from Image’Est on the Nancy tram system in 1929. This 46-minute documentary clearly demonstrates the performance and technical sophistication of this tram network, which reached its peak in 1925 with 12 lines and a total of 92 km of track. The film presents the tram network as an “essential tool for large modern cities” and “a fast, economical line of communication with the outlying suburbs”. However, the golden age of “all-tram transport” was short lived: in 1935, plans to replace trams with buses were already being made in Nancy. Work to dismantle the tram network started before the war, then speeded up thereafter.

Another example of the network maturity phase can be found in the ARCHIPOP collection. This film shows the Hoverlloyd hovercraft operating in 1969, carrying cross-channel traffic between Calais and Ramsgate in England. This sequence clearly shows the performance of this amphibious craft, powered by aerostatic lift and air propellers. The passenger cabin and onboard hostesses gave travellers the impression of being on a plane. These cross-channel shuttles, which were faster than traditional ferries, were developed in the 1960s and reached their peak in the 1970s, offering very high standards of reliability and security. In October 2000, after 32 years of service, the hovercrafts made their very last crossing. Operating costs, kerosene consumption and competition from the Channel Tunnel, which was inaugurated in 1994, led to the downfall of this iconic craft that marked Franco-British history.

– Network decline phase (4)

The most dramatic and touching film in the selection shows the decline of the barge industry in 1985. This short documentary from the Centre Audiovisuel Simone de Beauvoir gives inland waterway workers the chance to speak out about the current labour dispute. The bargees talk about how hard their work is and mention the “unfair” competition from trains and the heavily-subsidised SNCF rail network. “Paris will make a beautiful graveyard for boats.” In the heart of the French capital, the plight of the bargees, who live and work on boats with their families, contrasts with the “Bateaux-mouches” river cruises for tourists.

Our selection also touches on another form of decline, this time local train services in rural areas. This film from the Cinémathèque de Bretagne (1966) depicts a Sunday train journey in Brittany to the beaches on the Crozon peninsula. Although the short film shows how attached local people are to this old steam engine puffing slowly along its ageing track, this will not be enough to save the train. And yet it truly seems timeless and part of the scenery. The line was closed and dismantled just two years after the film, in 1968. At the time, the “capillary” rail network was being rapidly scaled back, as shown in Christophe Mimeur’s thesis.[5] Coincidentally, the same year that Jean Lazennec’s film was released, the SNCF launched a study on the “potential for very high speed rail services on new tracks”, which resulted in the TGV entering service in 1981. What a contrast!

One film shows the transformation of a network: this documentary from Fondation Autrefois Genève (1963) presents the activities of Compagnie Genevoise des Tramways Électriques and its complementary network of trams, trolley-buses and buses, which were modern for their time. During this period, almost all the tram lines were closed and replaced by buses, which were more flexible to operate: “Only 2 tram lines remain: the ring line and line 12.” For transport companies, buses have the advantage of low infrastructure costs, since public authorities are responsible for road maintenance. Buses are also flexible, and can change route without needing rails and overhead lines, which is another positive feature.[6] In 1969, line 12, which appears in this film, was the network’s last remaining tram line due to high passenger numbers. Today, it is the oldest functioning tram line in Europe. One sign that history sometimes falters: following this period of decline, the Geneva tram network entered a new phase of development during the 1990s.

– Network closure phase (5)

Tram networks declined until they completely disappeared from most urban areas in France. One example is the last tram running in Nancy from the Image’Est archive. In 1958, the whole tram network was permanently closed, after 84 years of service. French tram networks were dismantled until the 1960s, due to several factors: the positive image of buses, competition for space on streets with cars, as well as financial, regulatory and land planning issues (housing transformations). These films are here to preserve transport heritage, and this heritage allows us to cast a critical eye over progress in the mobility sector.

To conclude, the archives shared on the Amorce platform allow us to see the “invisible” side of transport: “Do city and country dwellers ever ask themselves how much effort is required for a vehicle to arrive on time, every day, to serve thousands of passengers?” (Excerpt from a film, Fondation Autrefois Genève, 1963). Numerous audiovisual archives show the hidden face of transport professions in offices, workshops and depots, where teams work to ensure operations, movement, repairs, track maintenance and electrical power. This film heritage enables us to see how important these agents are; transport would be impossible without them. There have, of course, been major changes in transport professions as networks developed (incubation, launch, initial development, maturity, decline, closure), resulting in disputes on working conditions. Two examples are bargees (Centre audiovisuel Simone de Beauvoir, 1985) and striking rail workers in Gare de l’Est, Paris (Ciné-Archives, 1968).

Most importantly, these archives invite us to take a step back and look closely at progress in the transport sector. Each period conveys values and representations that our society rarely takes time to understand. What sort of progress are we talking about? Progress to enable everyone to have a fuel-driven car? Progress resulting in the excessive motorisation of rural agriculture? Progress where buses have relegated trams to urban transport museums? Progress so that major networks (high speed railways, wide-gauge waterways) take precedence over local transport services? Every passing era brings a progress mechanism that is difficult to slow down or challenge. That’s why heritage - including the film heritage here - is important to reconsider our current choices in the light of past lessons.

[1] https://journals.openedition.org/ephaistos/7696

[2] https://www.persee.fr/doc/spgeo_0046-2497_1987_num_16_3_4241

[3] https://www.persee.fr/doc/flux_1154-2721_1993_num_9_13_960

[4] https://shs.cairn.info/histoire-des-transports-et-des-mobilites-en-france--9782200634315

Baldasseroni, L., Faugier, É. et Pelgrims, C. (dir.) (2022). Histoire des transports et des mobilités en France : XIXe-XXIe siècle. Armand Colin.

[5] https://theses.hal.science/tel-01451164v2/file/these_A_MIMEUR_Christophe_2016.pdf

[6] https://shs.cairn.info/histoire-des-transports-et-des-mobilites-en-france--9782200634315

Baldasseroni, L., Faugier, É. et Pelgrims, C. (dir.) (2022). Histoire des transports et des mobilités en France : XIXe-XXIe siècle. Armand Colin.