CARTE BLANCHE “20TH CENTURY SPORT THROUGH THE LENS OF AMATEUR FILMS: A MYRIAD OF MEMORIES” - BY THOMAS GOUBIN, SPORTS JOURNALIST

Sport only really became a mass social phenomenon in the 20th century. In France, we could even say that it started to conquer the country’s hearts and minds as of 1906. Although cycling races drew crowds from the end of the 19th century onwards, it was only when Sunday became a day of rest that society truly started to think about how workers could spend their leisure time. Everyone saw the advantages of sport, especially after the eight-hour day was adopted in 1919. For Catholic parish youth clubs, running around sports fields or perfecting movements in a gymnasium were healthy activities that helped curb sexual impulses, while employers viewed sport as a way to make workers more productive, keep them away from bars and foster a team spirit. Or even a way to divert their attention. “Get workers to play sports. While they’re playing, they won’t be thinking about trade unions,” said Henry Ford. For workers’ organisations, sport was also a means to recruit members and maintain the strength of working-class people. Although secular federations were initially reticent about sport - they thought building muscle would detract from cultivating the mind - they ended up adopting it too. (This dual perspective is still part of French culture today, though to a lesser extent.) Sport clearly won the match between the competing interests within these organisations, which nevertheless united behind three objectives: “public health, proselytism, recreation”. (1) A new wave had started to form, which was set to grow and gather momentum.

Alongside the tidal wave of media coverage generated by the 2024 Olympic Games in France, the mosaic of films collected by the 19 film libraries and archives in the Diazinteregio network, and shared on the Amorce platform, is particularly valuable: they remind us that sport is so much more than just competitive sports. They demonstrate that this major social phenomenon is multi-faceted (from catch wrestling to skateboarding, self-defence or swimming), primarily amateur, and shapes the daily lives of the French population: In 2000, 14 million people were licensed members of sports clubs, and 83% of 15 to 75 year-olds played sports, according to a study by the Ministry of Sport and INSEP. Other studies cited lower figures,(1) demonstrating the debate about how to define sport. The most generous definition, which has been chosen by Diazinteregio, is that sport is simply physical activity. This makes Geneviève, a young woman filmed having a swim on Dieppe beach in 1934, a sportswoman (Le bain de Geneviève, Normandie Images). A more restrictive definition of sport is: “a set of physical exercises that take the form of individual or collective games, which are played according to certain specific rules, and which generally give rise to competition” (Larousse).

Sport is also a performance for spectators. Catch wrestling is depicted in a particularly explicit manner, through the ropes of the ring, in Match de Catch, 1957, Cinémathèque de Saint-Etienne. The film portrays this clown-like mock combat, and the true physical prowess of its stocky wrestlers, who are as supple as gymnasts. The discipline was particularly appreciated by the French public during the thirty “golden” post-war years. Money started to circulate around stadiums, rings and gymnasiums... Sport became a way of earning a living, and its economic impact continues to grow (around 2% of French GDP in 2000). The battle between the proponents of amateur and professional sports was quickly won by the latter, even though several strongholds continued to resist (rugby officially became a professional sport in 1995, and the Olympic Games finally ended the myth of a strictly amateur competition in 1992). The Tour de France, which was created in 1903 by L’Auto newspaper (a former version of L’Equipe), never concealed that it was both a commercial business and a high-level competition. But this free cycling event also drew thousands of spectators, taking advantage of their summer holidays to line the roads, sandwich in hand, as shown in the film Col du Galibier, (1969, Cinémathèque des Pays de Savoie et de l'Ain). This marked the dawn of the leisure society - led by sporting activities - that followed the Popular Front’s social triumphs: paid holidays, the 40-hour working week. Faced with the threat of fascism, the labour movement joined forces in 1934 (before the left-wing parties) to form a sporting union, the Fédération Sportive et Gymnique du Travail (FSGT), a merger of the Communist FST and Socialist USSGT movements. Sport was seen to represent freedom, but at the same time, Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany instrumentalised sports - at the 1934 World Cup and the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin - by venerating the body as a metaphor for powerful nations, full of gladiators ready to die for their country.

After the war, when works councils were introduced (1946), employees inherited the management of social and sporting activities. Sport also became “corporate”. Filmed on various industrial sites and mines in the Meurthe-et-Moselle region, the film Sport et Travail (1950, Image'Est) depicts young workers as they train for running races and ball sports, in the middle of an ironworks, just beneath the blast furnaces. Sport was viewed as a social victory or a fundamental right.

Municipalities also played an important role in sports policy, by funding stadiums and other training facilities in cities like Brest, which was devastated during the war. The film La piscine de Tréornou, (1951, Cinémathèque de Bretagne), portrays leisure and competitive sports facilities that are open to everyone. However, it was only in the 1960s, when the sports budget was substantially increased, that the undeniable lack of equipment could at last be addressed. In fact, wider access to sport was triggered by the failure of the sporting elite: when France won no gold medals at the Rome Olympic Games, General de Gaulle asked the mountaineer Maurice Herzog (the High Commissioner then Secretary of State for Youth and Sport from 1958 to 1965) to lead a sports development programme. Tréornou benefited from this policy, with funding for a covered swimming pool that was inaugurated in 1966.

Sport is such an integral part of daily life and social interaction that you can always make space for it - even among the building sites when the Parisian suburbs were under construction. This is shown in the parallel scenes of the film Union des Sections Omnisports de Bezons (1975, Cinéam). Sport also conquered new ground. Filmed in the 1940s, L'apprentissage du ski (CimAlpes) harks back to the “age of innocence” before skiing and tourism became such big business. Every environment offers recreational pleasures, and new disciplines are constantly being created. Imported from the United States, skateboarding is a sport that doesn’t require a coach, just a stretch of pavement to play around on. Even so, this urban counter-culture has now been partially “tamed” into skateparks, and is now an Olympic discipline: “Skateboard” à Arras, 1982, Archipop). At the opposite end of the century, L’Auto-Vélo newspaper, which became L’Auto in 1903, announced in its first editorial that “every day, it would valiantly sing the praises of athletes and industrial triumphs”. This is because sport also involved mechanical prowess (Grand Prix Motor racing, 1946-1948, FAG). The quest for speed not only boosted innovation in the automobile industry, but also provided advertising space, to promote car manufacturers and their sponsors.

Women were often excluded from sport and left on the sidelines, despite the efforts of pioneers like Alice Millat. They had to break down many barriers and fight deep-rooted prejudice before they could fully occupy the sporting arena (in 2000, 79% of women declared that they took part in a sporting activity, even though they represent less than one third of licensed club members). In the film Fem Do Chi, self-defense pour femmes (1984, Centre Audiovisuel Simone De Beauvoir), women who had suffered domestic abuse learn fighting techniques, so they can defend themselves and regain control over their lives. Today, we would refer to this as “empowerment”. But discrimination still exists. Although sport can provide a break from daily life, it can never escape the flaws and attitudes of its time, even though television coverage - which now proudly stages sporting events - tries to reshape both sports and our experience of them.

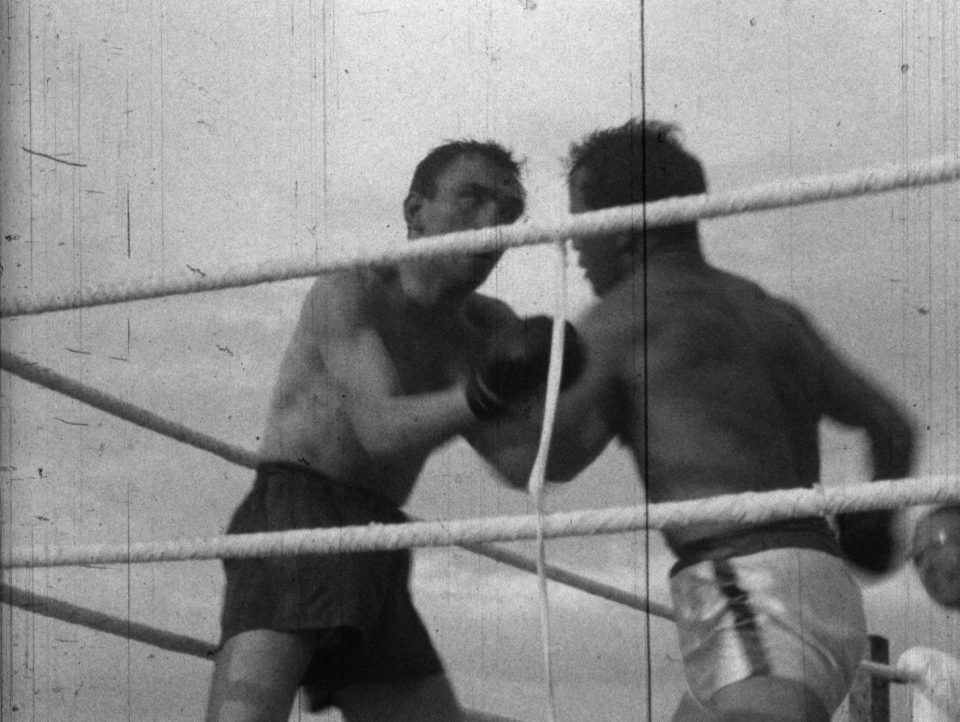

This is one of the strengths of the shared collection of films on the Amorce platform: they allow us to see way beyond the television cameras, by demonstrating how rich and varied sport can be. In addition, the amateur film-makers have chosen to show what happens behind the scenes, placing sporting tournaments in their social context, rather than in a competitive bubble of sensationalism. These mostly silent movies have a beauty of their own, and surprisingly they allow us to more fully feel, rather than hear, the intense efforts or violent blows (Matchs de boxe à Vierzon, 1956 CICLIC, Joutes nautiques devant le palais des Rohan, 1956 MIRA). Silent films also remind us that, for a long time, sports commentaries were mainly written, before being broadcast on the radio. Sport had a profound impact throughout the 20th century: sport for fun or competition, in amateur or professional clubs, from the French countryside to international events. This wider perspective does not reduce sport to “higher, faster, stronger”.

1. “FSGT : du sport rouge au sport populaire”, directed by Nicolas Kssis, La Ville Brûle editions, 2014.

2. Patrick Mignon. Les pratiques sportives : quelles évolutions ? Les Cahiers français : documents d’actualité, 2004, 320, pp.54-57.